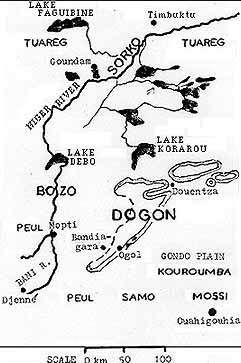

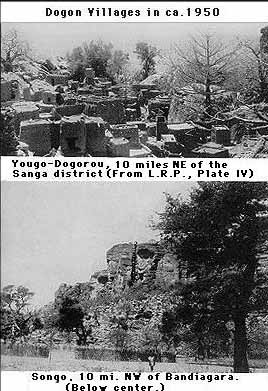

The Dogon are an ethnic group located mainly in the administrative

districts of Bandiagara and Douentza in Mali, West Africa.

This area is composed of three distinct topographical

regions: the plain, the cliffs, and the plateau.

Within these regions the Dogon population of about 300,000 is most heavily concentrated

along a 200 kilometer (125 mile) stretch of escarpment called the Cliffs of Bandiagara.

These sandstone cliffs run from southwest to northeast, roughly parallel

to the Niger River, and attain heights up to 600 meters (2000 feet).

The cliffs provide a spectacular physical setting for Dogon villages built on the sides of the escarpment.

There are approximately 700 Dogon villages, most with fewer than 500 inhabitants.

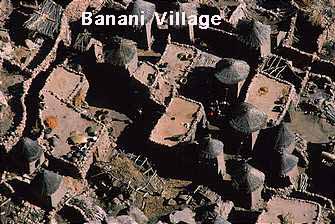

A Dogon family compound in the village of

Pegue is seen from the top of the Bandiagara escarpment. During the hot

season, the Dogon sleep on the roofs of their earthen homes.

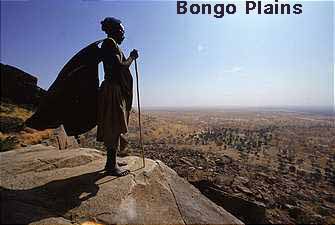

Abdule Koyo, a Dogon man, stands on the

top of the Bandiagara escarpment that overlooks the Bongo plains. As the

rocky land around the Bandiagara has become less and less fertile, the

Dogon have moved farther from the cliffs. Millet cultivation is more

productive in the fertile Bongo plains.

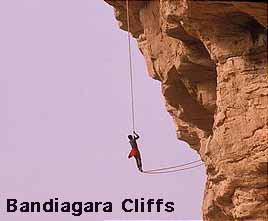

Without any equipment but his own muscle

and expertise, a Dogon man climbs hundreds of meters above the ground.

Ireli villagers use ropes made of baobab bark to climb the Bandiagara

cliffs in search of pigeon guano and Tellem artifacts. The pigeon guano

is used as fertilizer and can be sold at the market for $4 per sack. The

Tellem artifacts, such as brass statues and wooden headrests, bring

high prices from Western art collectors.

The precise origin of the Dogon, like

those of many other ancient cultures, is undetermined. Their

civilization emerged, in much the same manner as ancient Sumer, both sharing tales of their creation by gods who came from the sky in space ships, who allegedly will return one day.

The early histories are informed by oral

traditions that differ according to the Dogon clan being consulted and

archaeological excavation much more of which needs to be conducted.

Because of these inexact and incomplete

sources, there are a number of different versions of the Dogon's origin

myths as well as differing accounts of how they got from their ancestral

homelands to the Bandiagara region. The people call themselves 'Dogon'

or 'Dogom', but in the older literature they are most often called

'Habe', a Fulbe word meaning 'stranger' or 'pagan'.

Certain theories suggest the tribe to be of ancient Egyptian

descent - the Dogon next migrating to the region now called Libya, then

moving on to somewhere in the regions of Guinea or Mauritania.

Around 1490 AD, fleeing invaders and/or

drought, they migrated to the Bandiagara cliffs of central Mali.

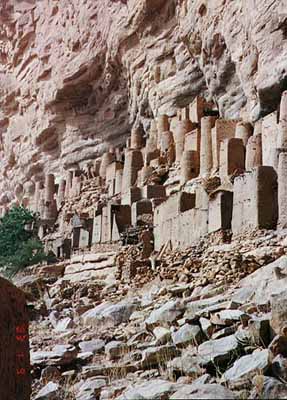

Carbon-14 dating techniques used on excavated remains found in the

cliffs indicate that there were inhabitants in the region before the

arrival of the Dogon. They were the Toloy culture of the 3rd to 2nd

centuries BC, and the Tellem culture of the 11th to 15th centuries AD.

The religious beliefs of the Dogon are

enormously complex and knowledge of them varies greatly within Dogon

society. Dogon religion is defined primarily through the worship of the

ancestors and the spirits whom they encountered as they slowly migrated

from their obscure ancestral homelands to the Bandiagara cliffs. They

were called the 'Nommo' - [see below and on the file Amphibious Gods.]

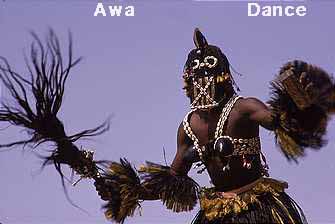

There are three principal cults among the Dogon; the Awa, Lebe and Binu.

The Awa is a cult of the dead, whose

purpose is to reorder the spiritual forces disturbed by the death of

Nommo, a mythological ancestor of great importance to the Dogon.

Members of the Awa cult dance with ornate

carved and painted masks during both funeral and death anniversary

ceremonies. There are 78 different types of ritual masks among the Dogon

and their iconographic messages go beyond the aesthetic, into the realm

of religion and philosophy.

The primary purpose of Awa dance

ceremonies is to lead souls of the deceased to their final resting place

in the family altars and to consecrate their passage to the ranks of

the ancestors.

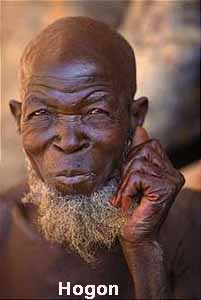

The cult of Lebe, the Earth God, is primarily concerned with the agricultural cycle and its chief priest is called a Hogon.

All Dogon villages have a Lebe shrine

whose altars have bits of earth incorporated into them to encourage the

continued fertility of the land.

According to Dogon beliefs, the god Lebe

visits the hogons every night in the form of a serpent and licks their

skins in order to purify them and infuse them with life force. The

hogons are responsible for guarding the purity of the soil and therefore

officiate at many agricultural ceremonies. [Serpent is a metaphor for

DNA]

In the village of Sangha, onion bulbs are

smashed and shaped into balls that are dried in the sun. The onion

balls are trucked as far away as the Ivory Coast to be sold as an

ingredient for sauces. Introduced by the French in the 1930s, onions are

one of the Dogon's only cash crop.

Millet Harvest - Dogon women pound millet

in the village of Kani Kombal. Millet is of vital importance to the

Dogon. They sow millet in June and July, after the rains begin. The

millet is harvested in October.

Nowadays, the Dogon blacksmiths forge

mainly scrap metal recuperated from old railway lines or car wrecks. So,

little by little, the long process of iron ore reduction, which demands

a perfect knowledge of fire and its temperatures, has been abandoned.

One of the last smelting was done in

Mali, in 1995, by the Dogon blacksmiths. The event became the subject of

a film which was entitled 'Inagina, The Last House of Iron'. Eleven

blacksmiths, who still hold the secrets of this ancestral activity,

agreed to perform a last smelt. They gathered to invoke the spirits.

They sunk a mine shaft, made charcoal,

and built a furnace with earth and lumps of slag. The last furnace - or

Inagina -meaning literally the 'house of iron' gave birth to 69 kilos of

iron of excellent quality. With this, the blacksmiths forged

traditional tools intended for agriculture, the making of weapons, and

jewelry for the Dogon people.

Youdiou Dances - During the Dama

celebration, Youdiou villagers circle around two stilt dancers. The

dance and costumes imitate the tingetange, a long-legged water bird. The

dancers execute difficult steps while teetering high above the crowd.

The cult of Binu is a totemic practice

and it has complex associations with the Dogon's sacred places used for

ancestor worship, spirit communication and agricultural sacrifices.

Marcel Griaule and his colleagues came to believe that all the major

Dogon sacred sites were related to episodes in the Dogon myth of the

creation of the world, in particular to a deity named Nommo.

Binu shrines house spirits of mythic

ancestors who lived in the legendary era before the appearance of death

among mankind. Binu spirits often make themselves known to their

descendants in the form of an animal that interceded on behalf of the

clan during its founding or migration, thus becoming the clan's totem.

The priests of each Binu maintain the

sanctuaries whose facades are often painted with graphic signs and

mystic symbols. Sacrifices of blood and millet porridge the primary crop

of the Dogon are made at the Binu shrines at sowing time and whenever

the intercession of the immortal ancestor is desired.

Through such rituals, the Dogon believe that the benevolent force of the ancestor is transmitted to them.

Kananga masks contain geometric patterns.

These masks represent the first human beings. The Dogon believe that

the Dama dance creates a bridge into the supernatural world. Without the

Dama dance, the dead cannot cross over into peace.

Their self-defense comes from their

social solidarity which is based on a complex combination of philosophic

and religious dogmas, the fundamental law being the worship of

ancestors. Ritual masks and corpses are used for ceremonies and are kept

in caves. The Dogon are both Muslims and Animists.

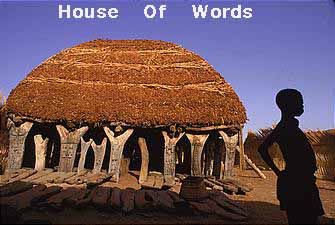

A 'Togu Na' - 'House of Words' - stands

in every Dogon village and marks the male social center. The low

ceiling, supported by carved or sculptured posts, prevents over zealous

discussions from escalating into fights. Symbolic meaning surrounds the

Togu Na. On the Gondo Plain, Togu Na pillars are carved out of Kile wood

and often express themes of fertility and procreation. Many of the

carvings are of women's breasts, for as a Dogon proverb says, "The

breast is second only to God."

Unfortunately, collectors have stolen

some of the more intricately carved pillars, forcing village elders to

deface their Togu Na posts by chopping off part of the sculpted wood.

This mutilation of the sculpted pillars assures their safety.

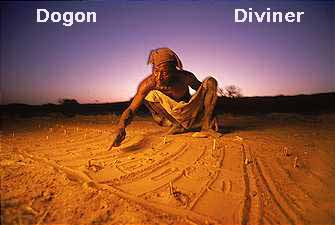

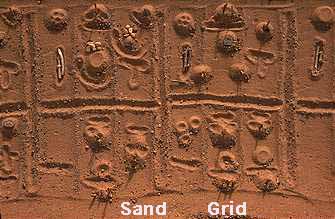

Amaguime Dolu, a diviner in the village

of Bongo, performs a ritual. He derives meaning and makes predictions

from grids and symbols in the sand. At dusk, he draws a questions in the

sand for the sacred fox to answer. The Dogon people believe the fox has

supernatural powers. The Dogon may ask questions such as: "Does the man

I love also love me?" or "Should I take the job offer at the mission

church?" In the morning, the diviner will read the fox prints on the

sand and make interpretations. The fox is sure to come because offerings

of millet, milk and peanuts are made to this sacred animal.

The Washington Post

Dogon Wikipedia

Nommo

Astronomy

The Dogon are famous for their

astronomical knowledge taught through oral tradition, dating back

thousands of years, referencing the star system, Sirius linked with the Egyptian goddess Isis.

The astronomical information known by the Dogon was not discovered and

verified until the 19th and 20th centuries, making one wonder how the

Dogon came by this knowledge. Their oral traditions say it was given to

them by the Nommo. The source of their information may date back to the

time of the ancient Egyptian priests.

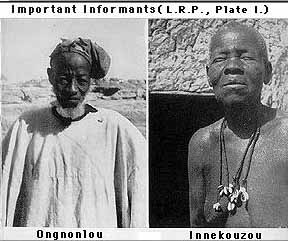

As the story goes ... in the late 1930s,

four Dogon priests shared their most important secret tradition with two

French anthropologists, Marcel Griaule and Germain Dieterlen after they

had spent an apprenticeship of fifteen years living with the tribe.

These were secret myths about the star Sirius, which is 8.6 light years

from the Earth.

The Dogon priests said that Sirius had a

companion star that was invisible to the human eye. They also stated

that the star moved in a 50-year elliptical orbit around Sirius, that it

was small and incredibly heavy, and that it rotated on its axis.

Initially the anthropologists wrote it

off publishing the information in an obscure anthropological journal,

because they didn't appreciate the astronomical importance of the

information.

What they didn't know was that since

1844, astronomers had suspected that Sirius A had a companion star. This

was in part determined when it was observed that the path of the star

wobbled.

In 1862 Alvan Clark discovered the second star making Sirius a binary star system (two stars).

In the 1920's it was determined that

Sirius B, the companion of Sirius, was a white dwarf star. White dwarfs

are small, dense stars that burn dimly. The pull of its gravity causes

Sirius' wavy movement. Sirius B is smaller than planet Earth.

The Dogon name for Sirius B is Po Tolo. It means star - tolo and smallest seed - po.

Seed refers to creation. In this case, perhaps human creation. By this

name they describe the star's smallness. It is, they say, the smallest

thing there is. They also claim that it is 'the heaviest star' and is

white in color. The Dogon thus attribute to Sirius B its three principal

properties as a white dwarf: small, heavy, white.

Nommo Description

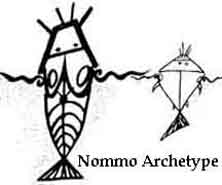

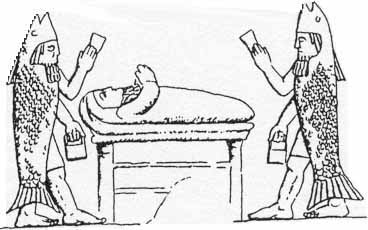

The Nommo are ancestral spirits

(sometimes referred to as deities) worshipped by the Dogon tribe of

Mali. The word Nommos is derived from a Dogon word meaning, "to make one

drink," The Nommos are usually described as amphibious, hermaphroditic,

fish-like creatures. Folk art depictions of the Nommos show creatures

with humanoid upper torsos, legs/feet, and a fish-like lower torso and

tail. The Nommos are also referred to as "Masters of the Water", "the

Monitors", and "the Teachers".

Amphibious Gods

Nommo can be a proper name of an

individual, or can refer to the group of spirits as a whole. For

purposes of this article "Nommo" refers to a specific individual and

"Nommos" is used to reference the group of beings.

Nommo Mythology

Dogon mythology states that Nommo was the

first living creature created by the sky god Amma. Shortly after his

creation, Nommo underwent a transformation and multiplied into four

pairs of twins. One of the twins rebelled against the universal order

created by Amma. To restore order to his creation, Amma sacrificed

another of the Nommo progeny, whose body was dismembered and scattered

throughout the world. This dispersal of body parts is seen by the Dogon

as the source for the proliferation of Binu shrines throughout the

DogonsÕ traditional territory; wherever a body part fell, a shrine was

erected.

In the latter part of the 1940s, French

anthropologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen (who had been

working with the Dogon since 1931) were the recipients of additional,

secret mythologies, concerning the Nommo. The Dogon reportedly related

to Griaule and Dieterlen a belief that the Nommos were inhabitants of a

world circling the star Sirius.

The Nommos descended from the sky in a

vessel accompanied by fire and thunder. After arriving, the Nommos

created a reservoir of water and subsequently dove into the water. The

Dogon legends state that the Nommos required a watery environment in

which to live. According to the myth related to Griaule and Dieterlen:

"The Nommo divided his body among men to feed them; that is why it is

also said that as the universe "had drunk of his body," the Nommo also

made men drink. He gave all his life principles to human beings." The

Nommo was crucified on a tree, but was resurrected and returned to his

home world. Dogon legend has it that he will return in the future to

revisit the Earth in a human form.

Controversy

In the 1970Õs a book by Robert Temple

titled The Sirius Mystery popularized the traditions of the Dogon

concerning Sirius and the Nommos. In The Sirius Mystery, Temple advanced

the conclusion that the DogonÕs knowledge of astronomy and non-visible

cosmic phenomenon could only be explained if this knowledge had been

imparted upon them by an extraterrestrial race that had visited the

Dogon at some point in the past. Temple related this race to the legend

of the Nommos and contended that the Nommos were extraterrestrial

inhabitants of the Sirius star system who had traveled to earth at some

point in the distant past and had imparted knowledge about the Sirius

star system as well as our own solar system upon the Dogon tribes.

Walter van Beek, an anthropologist

studying the Dogon, found no evidence that they had any historical

advanced knowledge of Sirius. Van Beek postulated that Griaule engaged

in such leading and forceful questioning of his Dogon sources that new

myths were created in the process by confabulation.

Carl Sagan has noted that the first

reported association of the Dogon with the knowledge of Sirius as a

binary star was in the 1940Õs, giving the Dogon ample opportunity to

gain cosmological knowledge about Sirius and the solar system from more

scientifically advanced, terrestrial societies whom they had come in

contact with. It has also been pointed out that binary star systems like

Sirius are theorized to have a very narrow or non-existent Habitable

zone, and thus a high improbability of containing a planet capable of

sustaining life (particularly life as dependent on water as the Nommos

were reported to be).

Daughter and colleague of Marcel Griaule,

Genevieve Calame-Griaule, defended the project, dismissing Van Beek's

criticism as misguided speculation rooted in an apparent ignorance of

esoteric tradition. Van Beek continues to maintain that Griaule was

wrong and cites other anthropologists who also reject his work The

assertion that the Dogon knew of another star in the Sirius system, Emme

Ya, or "larger than Sirus B but lighter and dim in magnitude" continues

to be discussed.

In 1995, gravitational studies indicated

the possible existence of a red dwarf star circling around Sirius but

further observations have failed to confirm this.

Space journalist and skeptic James Oberg

collected claims that have appeared concerning Dogon mythology in his

1982 book and concedes that such assumptions of recent acquisition is

"entirely circumstantial" and has no foundation in documented evidence

and concludes that it seems likely that the Sirius mystery will remain

exactly what its title implies; a mystery.

Earlier, other critics such as the

astronomer Peter Pesch and his collaborator Roland Pesch and Ian Ridpath

had attributed the supposed "advanced" astronomical knowledge of the

Dogon to a mixture of over-interpretation by commentators and cultural

contamination.

Nommo Wikipedia

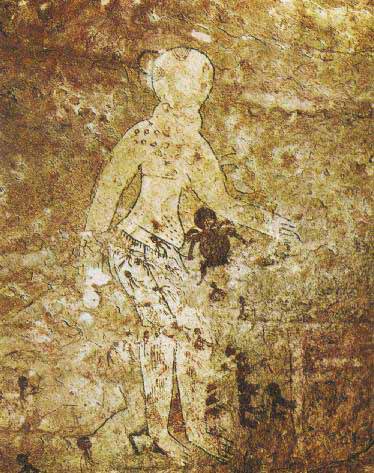

Tassili n'Ajjer, Sahara Desert, North Africa

Sahara rock art

is a significant area of archaeological study focusing on the precious

treasures carved or painted on the natural rocks found in the central

Sahara desert. There are over three thousand sites discovered that have

information about Saharan rock art. From the Tibesti massif to the

Ahaggar Mountains, the Sahara is an impressive open-air museum

containing numerous archaeological sites.

Tassili n'Ajjer

(meaning "Plateau of the Rivers") is noted for its prehistoric rock art

and other ancient archaeological sites, dating from Neolithic times

when the local climate was much moister, with savannah rather than

desert. The art depicts herds of cattle, large wild animals including

crocodiles, and human activities such as hunting and dancing. The art

has strong stylistic links to the pre-Nguni Art of South Africa and the

region, executed in caves by the San Peoples before the year 1200 BCE.

The range's exceptional density of rock

art paintings-pictograms and engravings-petroglyphs, and the presence of

many prehistoric vestiges, are remarkable testimonies to Neolithic

prehistory. From 10,000 BCE to the first centuries CE, successive

peoples left many archaeological remains, habitations, burial mounds and

enclosures which have yielded abundant lithic and ceramic material.

However, it is the rock art (engravings and paintings) that have made

Tassili world famous as from 1933, the date of its discovery. 15,000

petroglyphs have been identified to date.

Some of the painting have bizarre

depictions of what appear to be spacemen wearing suits, visors, and

helmets. resembling modern day astronauts. This takes us to the west

African tribe - the Dogon whose legends say they were guided to the area

from another part of Africa that was drying up - by fish gods called the Nommo who came in huge ships from the sky.

The Dogon and Sirius Mystery

La cosmogonie des Dogons (Mali)

The Tribal Eye: Behind the Mask

The Tribal Eye is a seven-part BBC

documentary series on the subject of Tribal art, written and presented

by David Attenborough. It was first transmitted in 1975.

1. “Behind the Mask”

This episode centers on the life and

customs of the Dogon people in Mali, concentrating primarily on their

masks and mask rituals. After a brief introduction to the Dogon culture,

the link between African and European art is elaborated upon, using

works by Picasso and Braque as examples. Dogon blacksmiths are shown

working on a sculpture and a monkey mask for an old woman’s funeral; the

funeral rites, which include masked performances and a staged mock

battle, are shown in great detail.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten