Researchers from Michigan State

University have discovered that plants have a rudimentary nerve

structure, which allows them to feel pain. According to the

peer-reviewed journal Plant Physiology, plants are capable of

identifying danger, signaling that danger to other plants and marshaling

defenses against perceived threats. According to botanist Bill Williams

of the Helvetica Institute, "plants not only seem to be aware and to

feel pain, they can even communicate."

This research has prompted the Swiss

government to pass the first-ever Plant Bill of Rights. It concludes

that plants have moral and legal protections, and Swiss citizens have to

treat them appropriately. The Penn State Vegetarians Club would do well

to investigate this data before claiming to be superior to those of us

who do not subscribe to the idea that eating meat is morally wrong.

Stephen Johnson

Plants Have Feelings!

One day, Backster connected a lie

detector to the leaves of a dracaena, commonly known as a “dragon tree.”

He wanted to see how long it would take for the leaves to react when he

poured water on the plant’s roots. In theory, a plant will increase its

conductivity and decrease its resistance after it absorbs water, and

the curve recorded on graph paper should have gone upward. But in

actuality, the line that was drawn curved downward. When a lie detector

is connected to a human body, the pen records different curves according

to the changes in the person’s mood. The reaction of the dragon tree

was just like the undulation of human mood swings. It seemed that it was

happy when it drank water.

Plants Have ESP

Backster wanted to see if the plant would

have any other reactions. According to past experience, Backster knew

that a good way to elicit a strong reaction from a person is to threaten

that person. So Backster dunked the leaves of the plant into hot

coffee. No reaction. Then he thought of something more terrifying: burn

the leaves that were connected to the lie detector. With this thought,

even before he went to get a match, a bullish curve rapidly appeared on

the graph paper. When he came back with a match, he saw that another

peak appeared on the curve. It was likely that when the plant saw he was

determined to start burning, it got frightened again. If he showed

hesitation or reluctance to burn the plant, the reactions recorded by

the lie detector were not so acute. And when he merely pretended to take

action to burn the leaves, the plant had almost no reactions. The plant

was even able to distinguish true intentions from false ones. Backster

nearly rushed out into the street to shout, “Plants can think! Plants

can think!” With this astonishing discovery, his life was changed

forever.

Later, when Backster and his colleagues

did experiments around the country with different instruments and

different plants, they observed similar results. They discovered that

even if leaves were picked off from a plant and cut into pieces, the

same reactions were recorded when these pieces were placed near the lie

detector electrodes. When a dog or an unfriendly person suddenly came

in, the plant reacted too.

Plants Are Experts at Detecting Lies

Generally for experiments involving lie

detectors, electrodes are connected to a suspect and then the suspect is

asked meticulously designed questions. Everyone has a clear-headed

side, which is usually called “conscience.” Therefore, no matter how

many reasons and excuses one gives, when lying or committing a bad deed,

that person knows clearly that it is a lie, a bad deed. Hence, the

body’s electric field changes, and this change is what is recorded by

the equipment.

Backster did an experiment in which he

connected the lie detector to a plant and then asked a person some

questions. As a result, Backster discovered that the plant could tell if

the person was lying or not. He asked the person what year he was born

in, giving him seven choices and instructing him to answer “no” to all

of them, including the correct one. When the person answered “no” to the

correct year, the plant reacted and a peak was drawn on the graph

paper.

Dr. Aristide Esser, the director of

medical research at the Rockland State hospital in New York, repeated

the experiment by asking a man to incorrectly answer questions in front

of a plant the man had nurtured and cared for since it was a seedling.

The plant did not cover up for its owner at all. Incorrect answers were

reflected on the graph paper. Esser, who had not believed Backster, saw

for himself that Backster’s theories were correct.

Plants Can Recognize People

In order to test how well a plant can

recognize things, Backster called on six students, blindfolded them, and

asked them to draw lots from a hat. One of the choices had instructions

to uproot one of the two plants in the room and destroy it by stomping

on it. The “murderer” had to do the deed alone, and no one else was to

know the culprit’s identity, including Backster. In that way, the

remaining plant could not sense who the “killer” was from other people’s

thoughts. The experiment was set up so that the plant would be the

exclusive witness.

When the remaining live plant was

connected to a lie detector, every student was asked to pass by it. The

plant had no reactions to five students. But when the student who had

committed the crime walked by, the electronic pen started drawing

frantically. This reaction indicated to Backster that plants are able to

remember and identify the person or thing that causes them harm.

Remote Sensitivity

Plants have close ties with their owners.

For example, when Backster returned to New York from New Jersey, he

found from the records on the graph paper that all his plants had

reactions. He wondered if the plants were indicating that they felt

“relieved” or were “welcoming” him back. He noticed that the time of the

plants’ reactions was the moment when he decided to return home from

New York.

Sensitivity to Life on a Microscopic Level

Backster discovered that the same fixed

curves would be drawn on the graph paper when plants seemed to sense the

death of any living tissue, even on the cellular level. He noticed this

by accident when he was mixed some jam into the yogurt he was going to

eat. Apparently, the preservatives in the jam killed some of the

lactobacilli in the yogurt, and the plants sensed this. Backster also

found that the plants reacted when he ran hot water in the sink. It

seemed they reacted to the death of bacteria in the drain. To test his

theory, Backster did an experiment and found that when brine shrimp were

put into boiling water via an automatic mechanism that did not require

human intervention, the plants had very strong reactions.

The Heartbeat of an Egg

Again by accident, Backster noticed plant

reactions one day when he cracked an egg. He decided to pursue this

experiment and connected the egg to his equipment. After nine hours, the

graph paper records indicated the heartbeats of an embryonic chick –

160 to 170 beats per minute – the same as a chick embryo that had stayed

in an incubator for three or four days. However, the egg was an

unfertilized egg that was bought from a store. There was no circulatory

system inside it either. How could Backster explain the egg’s pulse?

In experiments done at Yale University

Medical School during the 1930s to 1940s, the late professor Harold

Saxton Burr discovered that there were energy fields around plants,

trees, human beings, and cells. Backster thought Burr’s experiments

offered the only insight into his egg experiment. He decided to put his

plant experiments aside for a time to explore the implications of the

egg experiments and how his findings might relate to the issue regarding

the beginning of life.

The above article is summarized from these four articles from Zhengjian Net:

“Plants Can Think” – Exploration of the Secret Life of Plants I http://www.zhengjian.org/zj/articles/2001/3/9/9143.html

Plants Can Be Experts at Detecting Lies – Exploration of the Secret Life of Plants II http://www.zhengjian.org/zj/articles/2001/3/10/9196.html

Identifying the Murderer and Remote Sensing – Exploration of the Secret Life of Plants III http://www.zhengjian.org/zj/articles/2001/3/11/9197.html

No Difference Whether Life Is Big or Small – Exploration of the Secret Life of Plants IV http://www.zhengjian.org/zj/articles/2001/3/12/9198.html

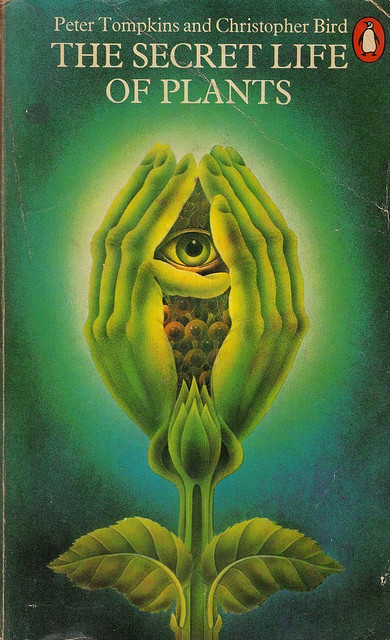

It means even on the lower levels of

life, there is a profound consciousness or awareness that bonds all

things together. Published in 1973, The Secret Life of Plants

was written by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird. It is described as

“A fascinating account of the physical, emotional, and spiritual

relations between plants and man.” Essentially, the subject of the book

is the idea that plants may be sentient, despite their lack of a nervous

system and a brain. This sentience is observed primarily through

changes in the plant’s conductivity, as through a polygraph, as

pioneered by Cleve Backster. The book also contains a summary of

Goethe’s theory of plant metamorphosis.

That said, this book is about much more

than just plants; it delves quite deeply into such topics as the aura,

psychophysics, orgone, radionics, kirlian photography,

magnetism/magnetotropism, bioelectrics, dowsing, and the history of

science. It was the basis for the 1979 documentary of the same name,

with a soundtrack especially recorded by Stevie Wonder.

what plants talk about

This

program integrates hard-core science with a light-hearted look at how

plants behave, revealing a world where plants are as busy, responsive

and complex as we are. From the stunning heights of the Great Basin

Desert to the lush coastal rainforests of west coast Canada, scientist

J.C. Cahill takes us on a journey into the “secret world of plants“,

revealing an astonishing landscape where plants eavesdrop on each

other, talk to their allies, call in insect mercenaries and nurture

their young. It is a world of pulsing activity, where plants

communicate, co-operate and sometimes, wage all-out war.

Scientists Confirm that Plants Talk and Listen To Each Other, Communication Crucial for Survival:

However, new research, published in the

journal Trends in Plant Science, has revealed that plants not only

respond to sound, but they also communicate to each other by making

“clicking” sounds.

Using powerful loudspeakers, researchers at The University of Western Australia were able to hear clicking sounds coming from the roots of corn saplings.

Researchers at Bristol University also found that when they suspended the young roots in water and played a continuous noise at 220Hz, a similar frequency to the plant clicks, they found that the plants grew towards the source of the sound.

Using powerful loudspeakers, researchers at The University of Western Australia were able to hear clicking sounds coming from the roots of corn saplings.

Researchers at Bristol University also found that when they suspended the young roots in water and played a continuous noise at 220Hz, a similar frequency to the plant clicks, they found that the plants grew towards the source of the sound.

“Everyone knows that plants react to

light, and scientists also know that plants use volatile chemicals to

communicate with each other, for instance, when danger – such as a

herbivore – approaches,” Dr. Gagliano said in a university news release.

“I was working one day in my herb garden

and started to wonder if maybe plants were also sensitive to sounds –

why not? – so I decided as a scientist to find out.”

While it has been long known that plants

grow towards light, previous research from Exeter University found

cabbage plants emitted methyl jasmonate gas when their surfaces are cut

or pierced to warn its neighbors of danger such as caterpillars or

garden shears.

Researchers from the earlier study also

found that the when the volatile gas was emitted, the nearly cabbage

plants appeared to receive the urgent message that and protected

themselves by producing toxic chemicals on their leaves to fend off

predators like caterpillars.

However, new research, published in the

journal Trends in Plant Science, has revealed that plants not only

respond to sound, but they also communicate to each other by making

“clicking” sounds.

Scientists suspect that sound and vibration may play an essential role in the survival of plants by giving them information about the environment around them.

Researchers said sounds waves are easily transmissible through soil, and could be used to pick up threats like drought from their neighbors further away.

Gagliano said that the latest findings shows that the role of sound in plants has yet to be fully explored, “leaving serious gaps our current understanding of the sensory and communicatory complexity of these organisms”.

In addition to other forms of sensory response, “it is very likely that some form of sensitivity to sound and vibrations also plays an important role in the life of plants,” she added

Scientists suspect that sound and vibration may play an essential role in the survival of plants by giving them information about the environment around them.

Researchers said sounds waves are easily transmissible through soil, and could be used to pick up threats like drought from their neighbors further away.

Gagliano said that the latest findings shows that the role of sound in plants has yet to be fully explored, “leaving serious gaps our current understanding of the sensory and communicatory complexity of these organisms”.

In addition to other forms of sensory response, “it is very likely that some form of sensitivity to sound and vibrations also plays an important role in the life of plants,” she added

The private life of plants

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten